Two Sides of the Same Coin: Turning Conflict Into Cohesion

Published

Conflict is a part of everyday life, and sports are no exception. Conflict in team settings may involve different factors, including, but not limited to, coaches, teammates, staff, and parents. To prevent and resolve team conflict, sport psychology consultants (SPC) need to understand how to promote team cohesion (Leo et al., 2015). This blog will discuss the different aspects of team conflict and team cohesion, and outline ways a SPC can transition conflict into cohesion.

Team Conflict

There are different types of conflict that can arise, particularly performance and relationship conflict (Holt et al., 2012). Performance conflict, centering around practice and competition concerns, can be functional to the team at moderate levels. This type of conflict can be useful if it encourages conversation and problem-solving among team members (Holt, et al., 2012). For example, players may disagree to the extent that others adhere to the training plan which can prompt discussion about changing the training plan to enhance improvement of all team members (Holt, et al., 2012). However, relationship conflict, which pertains to interpersonal disputes/disagreements between two or more teammates, is dysfunctional to team functioning (Holt, et al., 2012). Leo et al. (2015) found that collective efficacy levels fluctuate during a season, with team conflict playing a significant negative role, resulting in players lacking confidence in the team’s abilities.

Team Cohesion

Team cohesion can be broken down into task and social cohesion (Leo et al., 2015; Filho, 2015). To develop cohesion, coaches and sport professionals work to create a climate that fosters goal-directed behavior (task cohesion) and a feeling of togetherness among team members (social cohesion). In a study of adolescent volleyball players, Weiss et al. (2021) observed that athletes’ perceptions of higher task-involving climates, perceptions of coach climate (e.g., cooperative learning, role significance), and peer climate (e.g., effort, support, conflict) were related to task cohesion. Dimensions of coach and peer climates (e.g., coach’s emphasis on cooperative learning; teammates’ emphasis on relatedness support) were associated with social cohesion. Of note, task and social cohesion influence one another and have been shown to influence team performance and satisfaction (Eys, et al., 2015).

Perceived Challenges

When turning conflict into cohesion, SPCs need to consider personal and procedural factors, environmental factors, professional factors, and leadership factors (Wachsmuth et al., 2020; Filho, 2015). Gender is an example of a personal factor that has been found to influence team cohesion. Eys et al. (2015) observed that males were more likely to perceive cohesion from successful performance, while females may be more likely to perceive a performance successful by having a socially cohesive group. Environmental factors, such as the coach’s emphasis on cooperative learning and teammates’ emphasis on effort and relatedness, can also promote team cohesion (Wachsmuth et al., 2020; Weiss et al., 2021). Furthermore, leadership behaviors (e.g., feedback) can enhance or impair cohesions. For instance, the coach’s behavior has been shown to impact cohesion positively by creating higher levels of social support or negatively by coaches’ inability to change beliefs about how teams should be structured (Wachsmuth et al., 2020; Filho, 2015).

How Sport Psychology Consultants Can Help

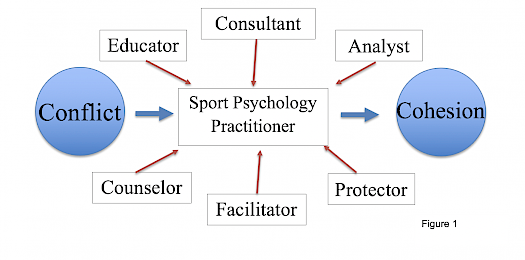

When it comes to a SPC’s role in managing coach-athlete or leader-follower relationships, there are a few different evidence-based approaches we can take. Holt et al. (2012) noted that there is no singular way to approach conflict, but the following strategies might facilitate a transition from conflict to cohesion: team building early in the season, addressing conflict early, mediation, and structured team meetings. As illustrated in Figure 1, Wachsmuth et al. (2020) found that SPCs can help to improve team functioning by taking on six different roles:

- Educator: educating athletes and coaches by providing information that they feel is important for prevention and conflict management;

- Consultant: consulting in utilizing long-term skill development and individualized problem-solving,

- Analyst and Action Planner: identifying and assessing explicit situations of conflict, analyzing the reasons, and developing strategies to manage them;

- Counselor: taking on a client-led approach to manage specific situations of conflict by working with only one of the relationship members;

- Facilitator: facilitating by forming bridges between conflicting parties, catalyzing conversations, and mediating and moderating conflict interactions; and,

- Protector: establishing and maintaining a healthy environment by noticing and managing dysfunction interpersonal processes as well as by ensuring that conflict agreements were adhered to or revised

Overall, team conflict has been shown to be a normative part of sports and may involve different factors, including, but not limited to, coaches, teammates, staff, and parents. There are two different types, performance and relationship conflict that may impact teams (Holt et al., 2012). To prevent and resolve team conflict SPCs need to understand how to promote team cohesion, whether that be focused on either task or social cohesion (Leo et al., 2015). Some perceived challenges when turning conflict into team cohesion may be differences in the gender of the athletes/team or the coaches’ behaviors (Eys et al, 2015; Wachsmuth et al., 2020; Filho, 2015). When transitioning team conflict into team cohesion, Wachsmuth et al. (2020) identified six different roles SPCs may take on: educator, consultant, analyst and action planner, counselor, facilitator, and protector.

References

Eys, M., Evans, M. B., Martin, L. J, Ohlert, J., Wolf, S. A., Van Bussel, M., & Steins, C. (2015).

Cohesion and performance for female and male sport teams. The Sport Psychologist, 29(2), 97-109.

Filho, E. (2015). Cohesion, team mental models, and collective efficacy: towards an integrated framework of team dynamics in sport. Journal of Sports Sciences, 33(6), 1–13.

Holt, N., Camilla, K., & Zukiwski P. (2012). Female athletes’ perceptions of teammate conflict in sport: implications for sport psychology consultants. The Sport Psychologist, 26, 135-154.

Leo, F.M, González-Ponce, I., Sánchez-Miguel, P.A., Ivarsson, A., & García-Calvo, T. (2015).

Role ambiguity, role conflict, team conflict, cohesion and collective efficacy in sport teams: A multilevel analysis. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 20, 60-66.

Wachsmuth, S., Jowett, S., & Harwood, C. G. (2020). Third party interventions in coach-athlete conflict: can sport psychology practitioners offer the necessary support? Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 1-26.

Weiss, M. R., Moehnke, H. J., & Kipp, L. E. (2021). A united front: Coach and teammate motivational climate and team cohesion among female adolescent athletes. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 16(4), 875–885.

Share this article:

Published in: